Khaleda Zia: A Stateswoman beyond Power

Staff Reporter

The hall at the National Press Club was heavy with silence, the kind that settles not from emptiness, but from memory. Beneath soft lights and rows of solemn faces, the name of Begum Khaleda Zia was spoken not as a former prime minister alone, but as a presence that still lingered—firm, compassionate, and deeply intertwined with the political journey of Bangladesh.

On Saturday, lawyers, rights activists and BNP leaders gathered at the Zahur Hossain Chowdhury Hall for a memorial meeting organised by the Lawyers’ Association and the World Human Rights Organisation Bangladesh, praying for the forgiveness of the soul of the former prime minister. What unfolded was less a formal programme than a collective act of remembrance.

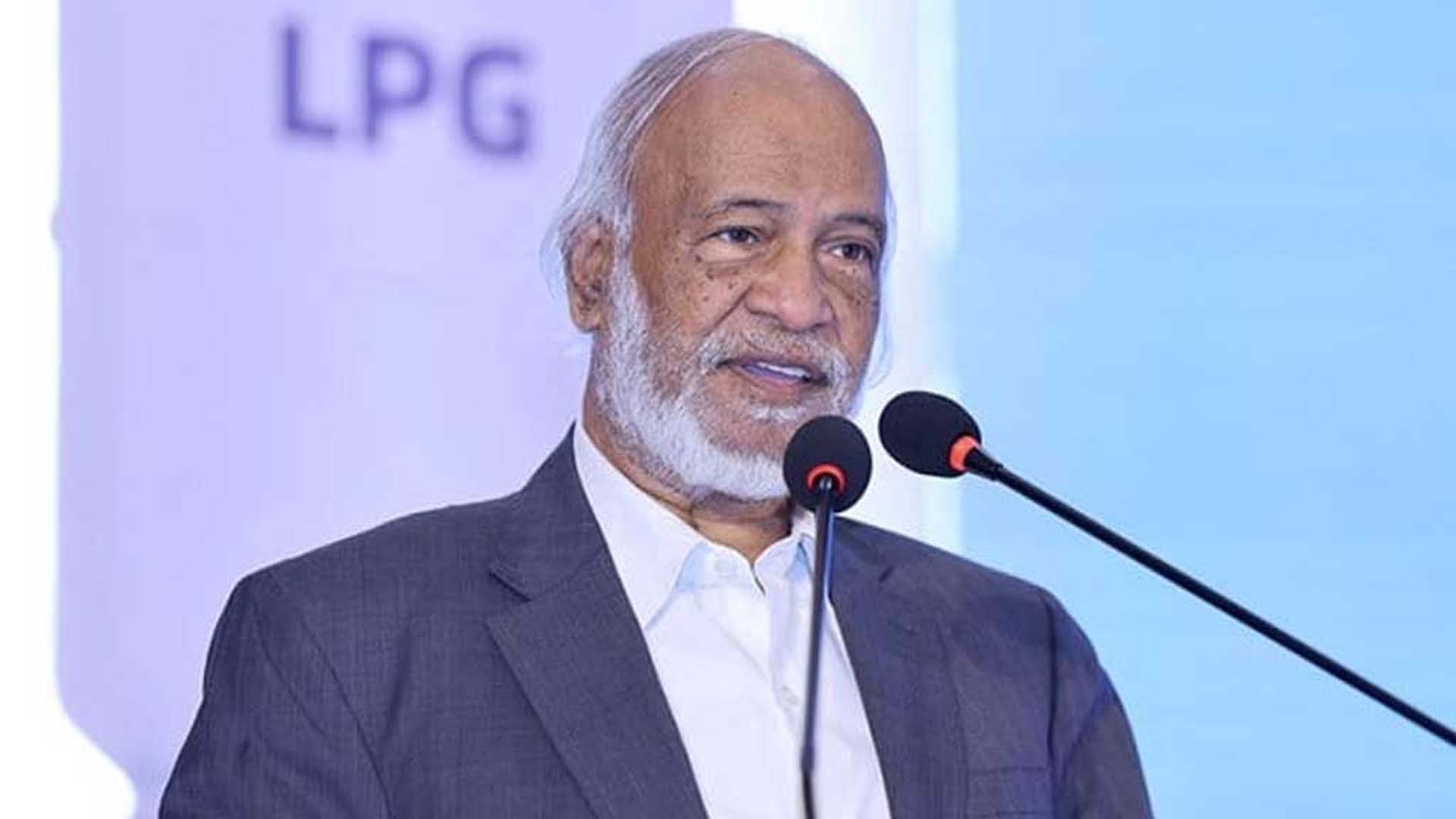

Dr Abdul Moyeen Khan, BNP standing committee member and former minister, stood before the audience and paused.

“I was thinking whether I am even qualified to speak about her,” he said. “Begum Khaleda Zia’s vast personality, her political wisdom, her generosity of mind and, above all, her immense love for the people of Bangladesh—one could speak for days and still not finish.”

He described her not merely as a political leader, but as a true stateswoman—shaped, he said, by thought, work, competence and an unmistakable humanity.

“Sometimes, when we try to speak about Begum Khaleda Zia, we become speechless,” Dr Moyeen Khan told the gathering. “When we remember her absence and her contributions, our voices choke. Even today, we struggle to find the language to express what we feel.”

For him, the memory of Khaleda Zia was inseparable from the turning point of the early 1990s, when Bangladesh was emerging from years of military rule. After the mass uprising of 1990, he said, Khaleda Zia appeared not as a cautious negotiator, but as an uncompromising leader. Her decision to boycott the 1986 and 1988 elections had drawn fierce criticism at the time. History, he argued, later vindicated her.

“It was that uncompromising position that paved the way,” he said, “and in 1991, the people of the country elected her as prime minister.”

Yet the portrait he painted was not only of political resolve, but of democratic temperament. Recalling his own years as a minister, including a term at the planning ministry, Dr Moyeen Khan said Khaleda Zia never once dictated how he should run his office.

“She gave me complete freedom. Not a single day did she instruct me to carry out a particular task,” he said. “That was her practice of democracy.”

He spoke of her unusual attentiveness even in matters of bureaucracy. Before appointing a senior secretary to a ministry, he recalled, Khaleda Zia had asked the concerned minister for his opinion—an act he described as a rare example of humility and respect for institutional process.

But it was perhaps his account of her response to persecution that drew the deepest silence from the room.

Referring to the dozens of cases filed against her, Dr Moyeen Khan said there were nearly 47 in total. He once asked her why she continued to appear in court so relentlessly.

“She told me, ‘They may act unjustly. But I cannot go outside the law,’” he recalled.In that brief sentence, he said, lay her reverence for law, her moral firmness, and her statesmanlike character.

“For this reason,” he added, “I firmly say Begum Khaleda Zia was a symbol of non-vindictive politics—a great stateswoman who truly practised democracy.”

As he spoke, listeners nodded quietly. Some closed their eyes. Others stared at the floor, as if searching through their own memories of rallies, movements, elections, imprisonments, and long political nights shaped by her presence.

The memorial meeting was also attended by BNP chairperson’s adviser Advocate Syed Moazzem Hossain Alal and several senior figures from the legal and human rights community. But the afternoon did not belong to speeches alone. It belonged to an idea: that leadership can be measured not only in victories and offices, but in restraint, in respect for institutions, and in the refusal to abandon law even when the law itself appears unjust.

Outside, the noise of Dhaka carried on as always. Inside, for a few hours, time slowed. And in that quiet space, Khaleda Zia was remembered not as a chapter closed, but as a moral reference point—of dignity in power, and of politics practiced without vengeance.