American Investment in UN Peacekeeping in Disarray with Niger Coup

Special Report :

On July 26, elite officers from Niger’s presidential guard let by General Abdourahmane Tchiani , detained Niger’s elected president, Mohamed Bazoum, and declared themselves the new leaders of the nation. This was alarming to the U.S. and European governments due to their close ties with Bazoum and Niger’s military, particularly concerning counter-terrorism activities against Islamist militants in the Sahel region.

General Abdourahmane Tchiani’s takeover is a stark reminder of the unpredictability in the West African region. The same general who once served under the UN peacekeeping banner, benefiting from U.S. funding and support, had now

detained President Mohamed Bazoum, the democratically elected leader of the country.

The UN doesn’t have its own military forces. Instead, Member States voluntarily supply the military and police personnel needed for peacekeeping operations. While peacekeeping soldiers are compensated by their respective governments based on their national rank and salary, the UN reimburses the contributing countries at a standard rate. As of 1 July 2019, this rate was US$1,428 per soldier per month. Payments for police and other civilian staff come from the specific budgets set for each peacekeeping operation. Additionally, the UN compensates Member States for equipment, personnel, and services they provide to support these contingents.

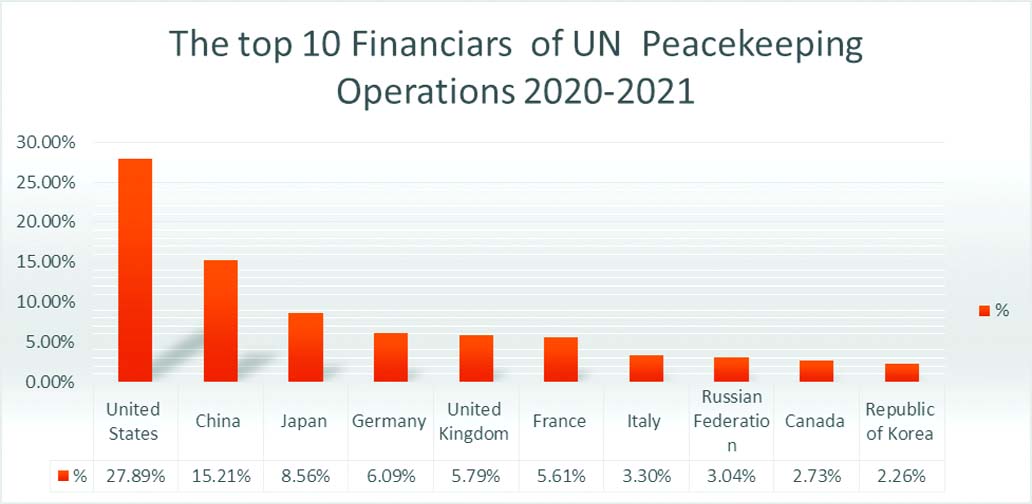

As the largest contributor to the UN peacekeeping budget, the United States has been a staunch advocate of peace and stability in the region. The coup, therefore, is not only a betrayal of Niger’s democratic institutions but also a deviation from the very principles that Gen. Tchiani once stood for during his peacekeeping days.

Despite his long-standing military background, bolstered by training in military academies from countries including the U.S., Gen. Tchiani seems to have surprised many. He emerged from a position designed to protect the president to declare himself the head of a military junta, which he named the National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland.

President Bazoum, meanwhile, remains isolated and under house arrest. US Deputy Secretary of State, Victoria Nuland, made a trip to Niger in hopes of initiating dialogue. However, her efforts were rebuffed, and she was denied an audience with Gen. Tchiani.

It is further troubling to see Niger’s junta leaders courting support from controversial groups and potentially ending defense agreements with traditional partners like France. Such actions can be perceived as a slight against long-standing international partnerships and threaten regional stability.

This episode shines a light on a broader challenge for U.S. foreign policy in West Africa. The U.S. has invested heavily in building peace and promoting governance in the region, and coups like these can disrupt our long-term objectives. Niger’s strategic importance in the fight against jihadist groups like Boko Haram means its stability is crucial, not only for West Africa but for U.S. security interests as well.

Moreover, as Gen. Tchiani navigates these tumultuous waters, riding on anti-French sentiments and testing his diplomatic skills against regional heavyweights, the U.S. will be closely watching. The balance between defending democratic values and maintaining regional stability is delicate, and the U.S. will need to calibrate its response thoughtfully.