The Fading Pulse of Ekushey: Is the Spirit Lost to Ritualism

Mir Abdul Alim :

As the dawn of February breaks, the haunting, soul-stirring melody of “Amar Bhaiyer Rokte Rangano Ekushey February” once again drifts through the alleys and airwaves of Bangladesh.

For those of us who grew up in the shadow of that sacrifice, the song was once a clarion call that ignited a fire in our veins. It wasn’t just a melody; it was our identity. Yet, as the years pass, that fire seems to be flickering into a faint, distant glow.

We are witnessing an unsettling metamorphosis where the raw, visceral connection to our linguistic roots is being replaced by a polished, hollowed-out corporate ritualism.

The unsettling reality is that the spirit of Ekushey- the defiant, blood-soaked soul of 1952 is fading into the backdrop of a globalized, indifferent landscape. What was once a movement for existence has now, tragically, become a calendar event?

The Cosmetic Commemoration a month of Pretense.We has reached a paradoxical juncture in our national history. Every February, we see a frantic, month-long obsession with “Bengali-ness.”

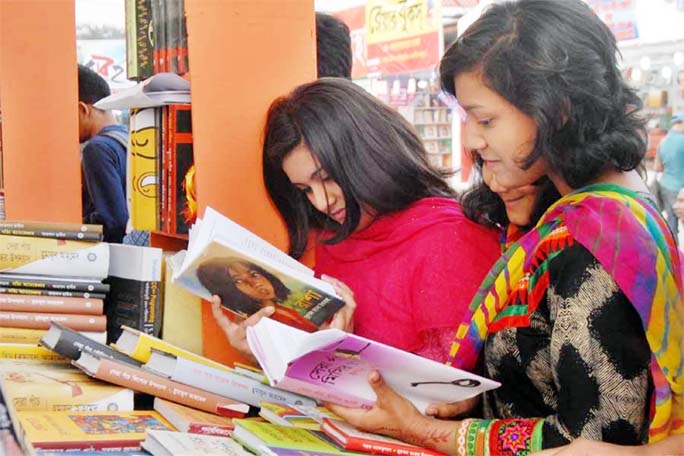

The Book Fair teems with crowds, and the Shaheed Minar is buried under mounds of floral tributes. Yet, for the remaining eleven months, we witness a slow, systematic surrender to linguistic erosion.

Our mother tongue has been relegated to the sterile pages of textbooks and the cold, silent stone of monuments.

Walk through the urban veins of Dhaka from the upscale blocks of Uttara to the historic heart of Shahbagh and the visual landscape tells a story of cultural displacement.

Our storefronts, high-rise digital billboards, and elite private universities are draped almost exclusively in English.

It is as if the Bangla script has become a burden too heavy or too “uncultured” for modern commerce to carry. We see “Biryani” butchered as “Birani” and “Vorta” misspelled on flashy signboards, reflecting a collective apathy.

Despite the High Court’s directives to prioritize Bangla in public signage, the defiance of these orders remains blatant and widespread.

The Invasion of the “Made Easy” Culture

Language is a living, breathing entity, but our version of it is currently being diluted by “beno jol” the brackish, invasive waters of hybridity.

History shows that during the Mughal era, our language absorbed Persian and Arabic terms like ‘Kurshi’ or ‘Sharbat’ with grace, enriching the vocabulary. However, today’s shift is different.

We are witnessing a chaotic “Banglish” culture where Hindi and English slang Janeman, Muzak, Nautanki, Dramabaji are seeping into the vernacular.

This isn’t enrichment; it is an erosion.

The modern Bengali seems to treat their language like an antique piece of furniture—something to be kept in a rusted tin box in a dark corner of an ancestral home, only brought out to display as a “heritage” tag when traveling abroad.

We wear the “Bengali” label like ivory: decorative and prestigious for the outside world, but ultimately detached from the living organism of our daily lives.

A Crisis of Identity in a Globalized Era

Over the last three decades, Bangladesh has undergone a radical transformation. We traded our gramophones for high-definition streaming and our “mud-tin” public buses for air-conditioned luxury.

We have traded the sprawling, chaotic warmth of joint families for the clinical privacy of “two-bedroom” apartments. Change is the hallmark of progress, and as a nation, we have proven our resilience and hunger for modernization.

But amidst this structural growth, did we ever consciously ask for the amputation of our linguistic soul? It is a heartbreaking irony that while Bangla stands as the sixth most spoken language in the world; its own practitioners at home suffer from a deep-seated linguistic inferiority complex.

The Medical Gap: Our brilliant doctors no longer write prescriptions in the language of the common people they heal.

The Legal Barrier: Our judiciary often argues that Bangla is “unsuitable” for the technical intricacies of legal judgments.

The Educational Divide: Our youth are being raised to feel a sense of “prestige” only when they distance themselves from their mother tongue, viewing English not just as a tool for communication, but as a badge of superior social class.

Beyond the Monument: The definition of “Bangla” is vast and inclusive. It encompasses the standardized formal tongue and the rich, melodic tapestry of dialects from Sylhet to Chittagong and Midnapore to Arakan.

It is the language that birthed a nation the only nation in history founded on the basis of a linguistic identity.

But if that nation no longer speaks its language with pride, what remains of that identity? As we stand barefoot before the Shaheed Minar this year, we must ask ourselves a difficult question: Is our presence there a tribute or a performance?

To the new generation, the educators, and the political leadership: the call is urgent. We must move beyond the “February frenzy.”

We must reintegrate Bangla into our technology, our boardrooms, and our daily social interactions. We must demand that our signboards reflect our soul and our schools teach our history with passion, not just as a syllabus requirement.

Let the spirit of Ekushey not be a ghost that haunts us once a year, but a living, breathing fire that guides how we speak, how we think, and how we claim our place in the world. Only then can we truly say that the blood of 1952 was not spilled in vain.

(The writer is a journalist and social researcher.

He can be reached at www.mirabdulalim.com)