News Analysis: Why Jamaat pushes a referendum and why BNP stays cautious?

Editorial Desk :

As Bangladesh moves through a politically sensitive transition, the national debate is no longer limited to when elections should be held.

Increasingly, the argument has shifted to a deeper question: what democratic safeguards should be built into the system before the next government takes office?

This shift explains why the proposal of a referendum on political reforms has become a flashpoint – especially inside the opposition space. Jamaat-e-Islami has taken a vocal position in favour of a referendum, often emphasising the need for reforms to be endorsed directly by citizens.

The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), in contrast, has appeared cautious, non-committal, or quiet on the proposal.

The difference is not simply about policy. It reflects a clash of political strategies shaped by timing, legitimacy, and the balance of power in a post-transition Bangladesh.

Why Jamaat pushes for a referendum

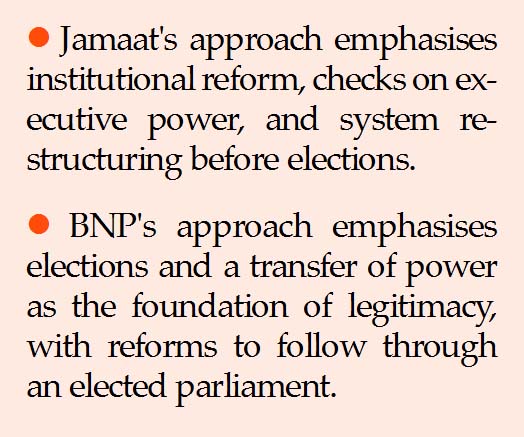

Supporters of Jamaat’s position argue that the party’s emphasis on a referendum fits a larger attempt to frame itself as a political force advocating “system change” rather than only electoral competition.

A referendum is attractive for several reasons.

First, it carries symbolic democratic legitimacy. A referendum is the most direct form of public participation: it allows citizens to approve or reject an issue without intermediaries.

In a country where trust in political institutions has been contested over multiple election cycles, Jamaat appears to believe that a referendum could give reforms a stronger moral mandate than parliamentary negotiation alone.

Second, a referendum reduces reliance on parliamentary seat strength. In Bangladesh’s first-past-the-post electoral environment, smaller parties often struggle to translate vote share into seats.

A referendum on reforms offers an alternative route to influence: if reforms are endorsed nationally, they become politically harder for future governments to ignore, even if Jamaat itself does not become a leading parliamentary force.

Third, it helps keep reform politics central. In transitional periods, political narratives can quickly narrow into a single issue – election timing.

A referendum proposal widens that agenda by forcing parties to speak on governance reforms, checks and balances, and institutional credibility.

In doing so, Jamaat positions itself as a driver of reform discourse and builds pressure on larger parties to respond.

In short, Jamaat’s insistence on a referendum can be read as an attempt to institutionalise reform before power changes hands, while simultaneously strengthening its national relevance.

Why BNP appears hesitant

BNP’s cautious posture does not necessarily mean outright opposition. Rather, the party’s strategy appears guided by its belief that the clearest route to restoring democratic legitimacy is through a national election and transfer of power.

Several factors may explain BNP’s hesitation.

First, BNP’s priority is election-first politics. BNP is widely considered the largest opposition force and is expected by many observers to perform strongly in a competitive election.

From that perspective, any additional political process – referendum campaigning, legal debates, administrative preparation – may be viewed as a potential complication that risks delaying elections or extending uncertainty.

For BNP, the strongest democratic mandate is still the ballot box.

A referendum, while democratic in form, could be seen as an added layer that shifts focus away from the core demand: a credible election.

Second, BNP may be wary of binding reform packages before parliament is elected. BNP’s position often stresses the principle that major structural reforms should be carried out through a representative parliament.

A referendum conducted before a parliament is formed can create a sensitive tension: it may lock in commitments that future lawmakers inherit without debate, limiting legislative flexibility and political bargaining once an elected government is in place.

In other words, BNP may prefer reforms – but on its preferred sequence: election first, reform next.

Third, BNP may be cautious about political narrative dynamics. The referendum issue is not ideologically neutral; it shapes public perception of who stands for “change” and who stands for “status quo.”

BNP may be calculating that a referendum-focused campaign could allow other parties to occupy the moral high ground of reform and accountability, while BNP risks being portrayed as reluctant or strategic.

For a party that has built much of its recent politics around legitimacy and democratic restoration, this is a delicate positioning problem: supporting a referendum could be interpreted as conceding to another party’s agenda, while rejecting it could be framed as blocking reform.

This likely explains BNP’s careful tone – neither fully embracing nor openly attacking the idea.

Note: This analysis reflects political interpretation based on publicly discussed positions and does not claim insider knowledge of party decision-making.