UN Water Pact: Dhaka’s move tests India’s bilateralism

Farrukh Khosru :

Bangladesh has become the first country in South Asia to join the UN Water Convention, a move that regional experts say could reshape the politics of river sharing and test India’s longstanding reliance on bilateral agreements.

Observers believe Dhaka’s step may encourage other South Asian nations, such as Nepal, Bhutan, and Pakistan, to consider accession, shifting the region towards a multilateral regime that India has long resisted.

On 20 June, Bangladesh formally acceded to the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes (Water Convention), a 1992 United Nations treaty that promotes equitable and sustainable sharing of rivers and lakes. Initially confined to Europe under the UN Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), the framework was opened to all UN member states in 2016 and now counts non-European parties such as Iraq, Namibia, and Ghana.

For Bangladesh, which relies on 57 transboundary rivers for its freshwater supply, accession is both a defensive and proactive measure. Seasonal floods devastate the country during the monsoon, while in the dry months, severe shortages threaten agriculture and food security. Officials argue that bilateral treaties with upstream neighbours have not adequately addressed these challenges.

“Bangladesh cannot afford to rely only on bilateralism when our very survival depends on the flows of the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna,” said Dr Muztaba Riza, a governance expert at Dhaka University. “The Water Convention gives us international leverage and a framework to push for equitable sharing and environmental safeguards.”

A senior official at Bangladesh’s Ministry of Water Resources, speaking on condition of anonymity, added that Dhaka had been “studying the treaty for over a decade” and concluded that it provides stronger institutional and technical mechanisms than the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention. “This is not about confrontation with India,” the official said, “but about preparing for a future where water demand and climate pressures will only grow.”

India, however, is not a party to either the Water Convention or the UN Watercourses Convention (UNWC). New Delhi has traditionally preferred bilateral arrangements, such as the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) with Pakistan and the 1996 Ganges Water Treaty (GWT) with Bangladesh. But these frameworks are under strain.

In April, India placed the IWT in abeyance after the Pahalgam terror attack, while the GWT is due for renewal in 2026. Reports suggest India may push for a fresh deal to account for irrigation and hydropower needs. West Bengal’s resistance to the 2011 Teesta agreement also highlights how domestic politics complicate New Delhi’s ability to deliver on water-sharing promises.

With Bangladesh moving towards multilateral frameworks, pressure is bound to increase. A Delhi-based foreign policy analyst, who asked not to be named, noted that the optics are troubling for India. “Suspending the Indus Treaty with Pakistan and hesitating over the Ganges renewal sends a signal of unwillingness to share water. Bangladesh’s accession to the Water Convention only amplifies that perception.”

“If India, long seen as a status-quo power in transboundary water governance, begins treating water as a strategic weapon, it opens the door for other states to follow suit”, said Ashok Swain, professor of peace and conflict research at Uppsala University in Sweden. He warns that India’s shift could undermine regional cooperation.

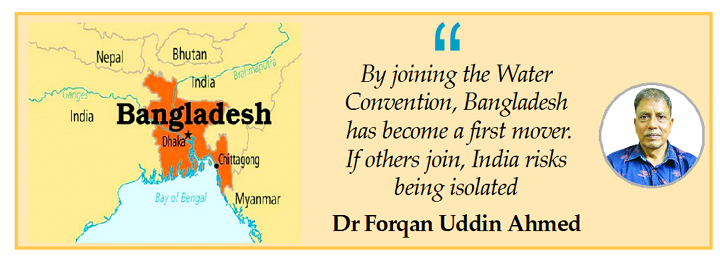

“South Asia has no basin-wide institution, no shared monitoring, and no legal enforcement for transboundary waters,” said Dr Forqan Uddin Ahmed, a former senior government official in Dhaka. “By joining the Water Convention, Bangladesh has become a first mover. If others join, India risks being isolated”, Dr Forqan told The New Nation.

China’s dam-building on the Brahmaputra (Yarlung Tsangpo) adds another layer of pressure. Both India and Bangladesh fear ecological risks from upstream developments, yet without regional coordination mechanisms, they remain vulnerable. India has responded by announcing its own dam on the Siang river, which experts warn could trigger further instability downstream.

The stakes are high as the 1996 Ganges Treaty approaches renewal. The current deal allocates 35,000 cusecs of water to each country in alternating 10-day blocks during the dry season. Bangladeshi officials argue that this arrangement no longer reflects the realities of climate stress, irrigation needs, and urban demand.

“Going forward, Bangladesh will press for environmental flows, transparent data-sharing, and a formal dispute resolution mechanism,” said the Ministry of Water Resources official. “The Water Convention strengthens our hand.”

Whether India adjusts its stance will determine the region’s future water politics. Himanshu Thakkar, a water expert and coordinator of the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People, said, “India must ask itself whether bilateralism, which worked in the past, can still serve in a climate-challenged, politically fragmented South Asia.”

For now, Bangladesh’s accession has set a new precedent – one that could push South Asia towards more cooperative, rules-based water governance, or deepen fault lines in an already fragile region.