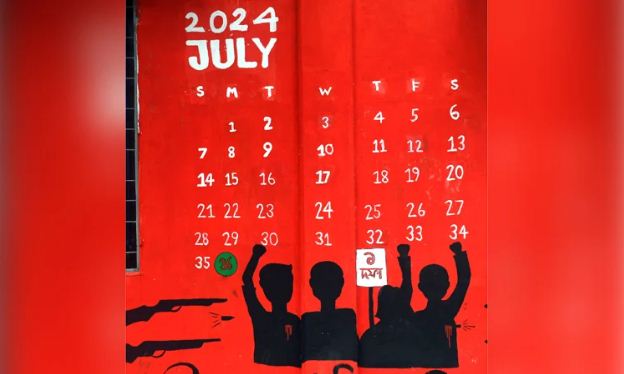

July 1 marked a turning point in the fall of AL regime

NN Online:

The first day of July last year saw an unprecedented surge in student protests that would ultimately evolve into a nationwide uprising, accelerating the fall of the nearly 16-year-long Awami League (AL) rule.

What began as demonstrations over a court verdict reinstating quotas in government jobs swiftly transformed into a broader “Anti-Discrimination Student Movement,” culminating in the “July Uprising” that drew in millions across the country.

Students initially took to the streets in outrage over a High Court ruling that overturned the government’s 2018 circular, which had scrapped quotas for first and second-class government officers. That 2018 decision came after massive student protests and had repealed the controversial 56% quota system, which included 30% for freedom fighters’ descendants and other reserved categories.

After the 2024 court verdict reinstated that system, students across the country viewed it as a betrayal of meritocracy. The response was swift. On July 1, student protests erupted nationwide. Within days, the protest evolved into a mass uprising demanding structural reforms and the end of what protesters called an increasingly autocratic regime.

The crackdown from law enforcement and pro-government groups was brutal. At least 1,400 people were killed and over 20,000 injured during weeks of clashes, according to estimates from protest organizers. Many saw this as the most violent state response to civil unrest since the country’s Liberation War.

However, the roots of the movement date back to June 5, 2024. That day, as news of the High Court order spread, frustration quickly grew among students. Asif Mahmud Shojib Bhuiyan, one of the movement’s central coordinators and now an advisor in the interim government, recounted in his book “July: Matribhumi Othoba Mrityu” that he learned of the verdict while getting his scooter repaired near Dhaka Medical College.

“As soon as I saw the news, I realized our struggle for meritocracy had been undermined. The achievements of 2018 were being undone,” Asif wrote. That evening, he and others called an emergency student meeting at the Dhaka University (DU) Central Library.

From there, a protest procession was organized under the banner of “Students of Dhaka University.” Sociology student Nahid Islam—who would later become the face of the movement and now leads the National Citizen Party (NCP)—declared a protest rally for June 6 at the Raju Memorial Sculpture.

Hundreds joined that first night, chanting slogans like “No to quota” and “Scrap the HC verdict.” Over the next few days, protests spread to major campuses: Jahangirnagar, Rajshahi, Chattogram, Jagannath, and others.

On June 9, student delegations submitted a memorandum to the Attorney General, urging a stay on the High Court order. That same day, the government filed an appeal with the Appellate Division, which set a hearing for July 4.

Meanwhile, students set a deadline: if the government failed to reinstate the 2018 circular by June 30, a full-scale movement would begin. The Eid-ul-Azha holidays delayed activities, but once campuses reopened on July 1, the protest reignited with greater intensity.

On July 1, DU students once again rallied under the new banner of the “Anti-Discrimination Student Movement.” From a rally at the Central Library, Nahid Islam announced a boycott of all classes and exams until July 4 and outlined a three-day protest program.

These included:

A mass procession on July 2

A student gathering at Raju Sculpture on July 3

A capital-wide mobilization on July 4 involving students from Jagannath University, National University colleges, and affiliated institutions

From that platform, Nahid also placed four key demands:

Immediate formation of a commission to reform the quota system to benefit truly disadvantaged groups

Unfilled quota seats to be filled by merit

Full transparency in the recruitment process

Ban on multiple uses of quota benefits in government recruitment exams

As students rallied peacefully, the state responded with extreme force. What followed over the next several days was a series of violent confrontations that resulted in a humanitarian and political crisis, shifting the protests from reform-based demands to a full anti-government uprising.

The July Uprising, which began as a fight for fairness in public service recruitment, became one of the most defining moments in Bangladesh’s political history. It signaled the collapse of a regime many had come to see as entrenched and unaccountable.