ICT’s historic verdict on crimes against humanity: Hasina sentenced to death

Abu Jakir :

In a landmark judgment that has reshaped Bangladesh’s political landscape, the International Crimes Tribunal-1 on Monday sentenced former dictator Sheikh Hasina to death for crimes against humanity committed during the July–August 2024 student uprising.

It is the most severe legal action ever taken against a former Bangladeshi head of government and marks an unprecedented moment in the country’s quest to address state violence.

The verdict was delivered in a tightly guarded Dhaka courtroom, as thousands of security personnel were deployed across the capital to avert unrest.

Hasina, who has lived in exile in India since her government collapsed during the mass uprising in August 2024, was tried in absentia after declining repeated summonses from the court.

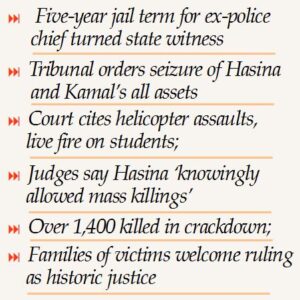

The three-member bench, led by Justice Golam Mortuza Mojumdar and comprising Justice Md Shafiul Alam Mahmood and Judge Mohitul Haque Enam Chowdhury, found overwhelming evidence that she authorised the use of lethal force, including helicopter and drone assaults, against unarmed demonstrators demanding her resignation.

According to the 453-page judgment released shortly after the hearing, Hasina “failed to prevent and punish state forces engaged in mass violence” and “knowingly allowed indiscriminate attacks on unarmed protesters,” actions the tribunal classified as crimes against humanity under domestic and international law.

The judges also stated that her refusal to return to Bangladesh to stand trial was “indicative of guilt” and “an attempt to evade accountability.”

Former Home Minister Asaduzzaman Khan received the same capital sentence for his role in directing police and paramilitary units during the crackdown.

Both he and Hasina had fled to India during the uprising.

In contrast, former police chief Chowdhury Abdullah Al-Mamun—who turned state witness, pled guilty, and provided detailed testimony regarding chain-of-command decisions—was sentenced to five years in prison.

The tribunal ordered the confiscation of all movable and immovable properties belonging to Hasina and Asaduzzaman Khan.

It also instructed the government to establish a compensation mechanism for the families of those killed and for survivors who were injured during the uprising.

Audio and video footage, depositions from survivors, and intercepted phone conversations featuring Hasina and senior officials were cited extensively in the judgment.

The court played several of these recordings during the final hearings, including conversations between Hasina and former Information Minister Hasanul Haque Inu, describing ongoing operations against protesters in Dhaka, Savar, Ashulia, Rangpur, Jatrabari, Rampura and Badda.

The tribunal noted that more than 1,400 people were killed during the crackdown, making it one of the deadliest episodes of political violence in Bangladesh’s history.

Witnesses described security forces firing live ammunition into crowds, conducting aerial attacks on protest hubs, and using armoured vehicles to disperse students who had joined the July uprising calling for justice, accountability and Hasina’s resignation.

The interim government reacted swiftly after the verdict. In remarks to reporters at the Secretariat, Law Adviser Professor Asif Nazrul said the ruling represented “the highest achievement of justice in Bangladesh’s modern history.”

He added that Dhaka would send a fresh formal request to New Delhi seeking the extradition of Hasina and Asaduzzaman Khan, though analysts anticipate prolonged diplomatic negotiations given India’s reluctance to repatriate political fugitives.

“The evidence presented in court would secure identical convictions in any jurisdiction in the world,” Nazrul said.

Chief Prosecutor Mohammad Tajul Islam echoed that view, praising the tribunal’s adherence to international norms.

“Bangladesh has demonstrated its capacity to conduct trials of complex crimes such as crimes against humanity. Any court in the world would have passed the same sentences based on these proofs,” he said.

The Awami League, however, denounced the verdict as “entirely political” and called for a nationwide hartal later in the week.

In a statement issued from exile, Sheikh Hasina rejected the charges as “fabricated” and described the tribunal as “a mechanism for vengeance engineered by those who illegally overthrew a constitutional government.”

Her party warned that the ruling would destabilize the country and undermine the credibility of the interim administration led by Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus.

International attention is now fixed on Bangladesh as the 2026 general election approaches.

Western governments, human rights organizations and regional observers are expected to scrutinize both the trial process and the broader political climate in the months ahead.

Extraditing Hasina from India—should the government continue to pursue it—could become a flashpoint in bilateral relations and may weigh heavily on regional geopolitics.

The verdict also signals broader implications for Bangladesh’s post-uprising political order.

For the first time, a former prime minister has been held criminally liable for state violence committed under her watch.

The ruling establishes a judicial precedent for accountability that could influence future governance, security-sector reform and transitional justice debates.

Beyond the courtroom, the judgment has reopened national conversations about the July uprising itself, which was live-broadcast from the tribunal as it unfolded on Monday.

Families of victims gathered outside the courthouse, many holding photographs of those they lost. Survivors described the verdict as long-awaited recognition of what they endured.

“This cannot bring back my brother,” said one protester from Rangpur, “but at least the truth is now acknowledged.”