Among other disciplines in the higher studies the subject ‘Gerontology’ specially social gerontology has not given sufficient attention to the degree to which age and aging are not socially constituted as a movement in our society and to the ways in which both age and aging are currently being transformed as a result of the set of social forces surrounding processes of globalisation.

The neglect of critical analysis has weakened attempts to understand the social processes involved in shaping age and the life course of the human beings.

Later, the creation of alternative conceptions and visions has developed about the future of old age.

This should be linked to gerontology and aging process to save the future generations.

Over the last half-century, social gerontology has been characterised by an imbalance between the accumulation of data and the development of theory in this discipline as Bengtson, Rice, & Johnson, 1999; Hendricks & Achenbaum, 1999; Riley & Riley, 1994 expressed earlier. Researchers interested in aging have relentlessly collected mountains of data, often driven by narrowly defined, problem-based questions and with little attention to basic assumptions or larger theoretical issues. An absence of theoretical development is surely not surprising for a fairly young enterprise that seeks to capture a complex empirical reality; especially one that draws from many disciplines, and that is preoccupied with urgent practical problems (Hagestad & Dannefer, 2001). Yet the lack of attention to theory has meant that research questions have often been informed by an uncritical reliance on images and assumptions about aging drawn from popular culture or from traditions and paradigms of theory that are considered outdated

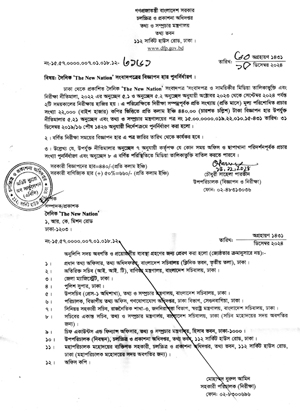

It is really a matter of proud for us that the tendency of research in Gerontology has started a few years ago and this discipline was mostly unknown to common people but in reality, this deemed a very important subject throughout the world. Besides the ensuing awful future we should have to take necessary measures for ensuring active and healthy aging environment at the later stage of life. Considering he situation and world-wide trend the Institute of Social Welfare and Research of the University of Dhaka has taken a epoch-making step to introduce this important discipline under the guidance of a group of devoted and learned teachers which include Prof Md Nurul Islam, Prof ASM Atiqur Rahman, Prof Habibur Rahman, Prof Kabir Associate Professors Dr Golam Rabbani, Dr Rabiul Islam, Dr Hafiz Uddin Bhuiyan, and Md Mainuddin Mollah, Sr Lecturer and others who have graced the institute regarding the education dissemination in this discipline. The first session was introduced in the 2012-2013 session i which I was a proud student of this discipline. 60 students were selected for this course, which is call, specialised Masters Degree in Gerontology & Geriatric Welfare (GGW). The first batch students have successfully completed their courses and their results are already published. Fifty-two students appeared and passed in the final examinations and the rate of passing is 100 per cent, which is a tremendous success of the institute in real sense. Actually, the teachers of these subjects was very dedicated and devoted to the development of the students. There is a very good feature of this course that had inspired me to take admission into this course that is there is no bar of age in taking admission into this specialised Masters programme that really attracted me in taking admission into this subject. But there are also an admission test and oral test for the selection process regarding admission of the students. This course comprised of 45 credits and has a vigorous examination system in the two semesters.

The Social Welfare Institute performs the whole responsibilities in conducting exams, research, assignments and presentations with the assistance of devoted teachers. We are really proud of this Institute in deed for their outstanding contribution throughout the management of the specialised Masters programme.

The word ‘Gerontology’ was totally unknown to me while I first saw the advertisement for admission in the national dailies. I was impressed and curious about gerontology while I researched on the subject through the Internet. I read about 100 of research papers on this before submission of admission application and I was finally inspired to get admission into this department. This is a very elaborative programme, which includes social science, arts, commerce, medical science, nursing, physiotherapy and many more. so, a diversified group of students availed the opportunity to exchange their views, ideas and notions during the research and group-works, assignments and presentations, class assignments, field visits and regular discussion sessions that has raised the efficiency, capabilities, skill in serving clientele groups and individuals who are in need of social, family and community support and ultimately achieving the capacity of the client to combat and solve their own problems.

Yilea Yilich, who first coined the word ‘Gerontology,’ which means ‘Geron’ = old and ‘ology’ means ‘scientific study,’ so the word denotes the meaning ‘Scientific Study of Ageing ‘ or older people. Now, the subject has a worldwide application throughout the world specially in the American and Western societies. The most of the developed countries are called the ‘ageing societies’ where 10 per cent or more people are under the older/elderly age group i.e. those people have crossed 60 chronological years.

The 2nd batch was already admitted and their classes are regularly held at the evening session in the Institute.

Further, several major gerontological paradigms of the late 20th century have contributed fundamental insights to inform theoretical development. These include, for example, the principles underlying cohort analysis and the interplay of demographic and economic forces, which in turn reflect the importance of history and social structure.

These paradigms have included age stratification (Riley, Johnson, & Foner, 1972), life-course theory (Elder, 1974), life-span development (Baltes, 1987), and the first paradigmatic source of critical gerontology, political economy (Estes, 1979; Minkler & Estes, 1999; Phillipson, 1982; Walker, 1980, 1981).

National policies in many countries relating to the health and social care of older people have never been so active in reality. Many organisation at national level working for older people underpin the Government’s national strategy for older people.

The strategy sets out a range of key targets including the role of person centred approaches to practice with older people, age based discrimination and addressing the current poverty of provision for mental health and other services for older people.

The development of subsequent policy has focused attention on key objectives which apparently seek to shift the manner in which services and practices are organised and delivered, and in so doing, create improved, flexible and ‘person centred’ services for older people.

The policies for the older people should highlight the following:

nSupporting independence, choice and control of the older persons.

nImproving quality of life, from the perspective of the ‘whole person.’

nEnsuring personal dignity and honour, employment and engagement in society.

nSupporting the active participation of older people in decisions in family, community, society and national level for their own safety, dignity and health care.

nGovernment should plan for integrated service delivery.

nDecide priority for older people in all steps of national life.

nHealth priority, living and life safety plan for the older people.

nRaise a competent group of older carers, volunteers, nurses, physicians, activists and active support groups.

nFormation of Older Persons Association with all available and necessary facilities.

nGerontological topics should be included in national education system and all level of syllabuses (primary to advanced level)

nCreating job opportunities in this service sector (all hospitals, clinics and medical centres)

nNational monitoring and evaluation cell for measuring progress and outcome

nCreating District-wise information cell and counselling and advocacy centres

nGovernment should come forward for the well-being of older persons in all respects.

Moreover, in many countries, there have been a flourishing development in research and evidence based ‘good practice’ guidance. The good practice guidelines for health and social care practice in dementia care (NICE/SCIE, 2006) highlight for example, the importance of holistic and person centred assessment practice, proactive approaches in responding to behaviour which is perceived as challenging; and comprehensive training to enable practitioners to deliver person centred care.

Dissemination of research which promotes the active participation of older people continues to develop the knowledge base on what older men and women value about services, the ways in which they are delivered and outcomes that are important to older participants.

Paradoxically, despite an apparently flourishing policy agenda, which increasingly articulates a notion of ‘good practice,’ major challenges exist in the current provision and delivery of social and health care services. These challenges reflect a dichotomy between on the one hand, an imperative to operate within a managerialist agenda and on the other, develop preventative and proactive, user focused and user led services. This certainly creates a difficult set of tensions manifested in terms of managing tightening eligibility criteria, responding to externally derived performance criteria and persistent reorganisations against a stated aspiration to provide good quality services for older people.

The consequences include that fewer people receive any form of services. Moreover, the emphases on responding to only those in greatest need, stymies attempts to develop any comprehensive response to the preventative agenda. Informal carers are also managing the consequences of reduced levels of provision.

This has raised a number of critical issues on the aged people, which require urgent discussion and debate. First, it is clear that social workers working with older people are managing increasingly complex workloads most of the times. If the preventative measures are to be taken seriously, then this will add to the demands for a skilled workforce with appropriate gerontological knowledge, skills and attitudes and values.

Assessment and intervention for older people with complex needs can create the experience of a negative or inadequate response to a person’s need. Moreover, such approaches can serve to reinforce negative assumptions about what older people need. Besides, in an environment where inter-agency collaboration is commonplace, social workers need to know and be confident about the knowledge, skills and values they bring to the table. There is, finally, a need to re-examine the knowledge and skill base in respect to working with older people.

For example, should the gerontological research and knowledge base be utilised to inform practice?

More or less, it is already proved that there is a major challenge facing social workers with older people caring process. Not only qualified social workers are disenchanted, social work students, previously committed to working with older people turned off’ by their experience on placement: social work with older people is ever more driven by ‘process’ with many complex tasks previously undertaken by qualified social workers being carried out by social care staff.

The advent of the new specialised social welfare degree of the Institute of Social Welfare and Research having with its emphasis on the application of research and the integration of knowledge, skills, values and practice offered the potential for the development of a more theoretical, evidence based, knowledge driven social work with older people along the lines of that pursued in other areas such as social work with children and young people or mental health social work. However this degree is a generic qualification and the extent to which ‘gerontological’ social work is addressed in those academic institutions that do not already have an interest in gerontology is questionable. Disappointingly, in the new post-qualification framework social work with older people is not regarded as a specialist subject area but is subsumed within ‘social work with adult,’ alongside younger adults, physical and sensory impairment, learning difficulties, chronic and/or terminal illness, drug dependency and people who may be HIV positive or have Aids. Again, the extent to which training in gerontological, rather than process-led training will be developed is open to debate as a whole.

Most of the social workers increasingly work alongside other professionals in multi-disciplinary settings or even across sectors, and this is particularly the case in social work with older people. To the contrary, in order to best advocate with, and for, older people social workers should be encouraged and supported in all respects to develop an identity that is located in specialist as well as generalist knowledge, shared values and anti-ageist practice and both traditional skills and those honed towards gerontological social work.

It is seen that, in the current climate, there has been a loss of both identity and confidence in social work with older people. Social workers have become resigned to their lot. We think it is time to ‘fight back’ to find ways of raising morale and restoring confidence amongst social workers working with older people and at the same time provide the highly skilled, multi-agency workforce that is necessary in order to ensure that those older people who make use of services are both included and best served.

It should be obligatory to start recognising the complexity of the work and the gerontological profession that are regularly pursued by social workers who work alongside older people and their families,caregivers and the way in which this mirrors many of the debates currently being addressed within the social gerontological community.

Constraints relating to gerontological activities such as service user involvement, identity, gender, ethnicity, disability, life-course transitions, family relationships and conflicts, loss and bereavement, management of autonomy in the face of change quality of life, as well as those relating to the management of crises resulting from ill-health, abuse and neglect. In addition, social workers support and enable carers, many of whom are also older people. Such complex work needs a sound evidence base of ‘good practice’ which is not just about ‘process,’ nor generalist social skills but should be rooted in specialist knowledge, skills and values and which enables social workers to uphold the rights of older people, better negotiate eligibility criteria and argue for resources.

It is viewed that such an evidence base already exists within the welter of social gerontological research but that it is not consistently being accessed by hard-pressed practitioners. Given the lack of specialist training in gerontological social work identified earlier, we would go further and argue that many social workers are not even aware of its existence.

Specialised Masters degree programme in Gerontology and Geriatric Welfare of Dhaka University (Institute of Social Welfare & Research) really inspire the students to gain new knowledge, skill, views, outlook and insight on the activities of ensuring overall well-being in the work practice. So, these batches of students can play a very pivotal role in combating the awful situation in the forthcoming future and could solve many socio-gerontological problems by exerting valuable knowledge and skills in the development of gerontological processes, approaches, services, policies, techniques and practices (both family, group and individual level) towards the betterment of the older people of Bangladesh. Needless to say that research and gerontological debates, symposiums, seminar and establish training programmes for the gerontological activists who can put effective contribution in the fulfilment of well-being of the older people in the years to come.