Forgotten story of Bangladesh’s Urdu-speaking community

Mohammad Hasan :

In the context of Bangladesh, the Urdu-speaking community represents a distinct ethnic and linguistic origin group. Commonly referred to as “Biharis”, this term reflects the widespread belief that the members of the community migrated solely from the Indian state of Bihar in the aftermath of communal riots and violence following the 1947 partition of the Indian subcontinent.

However, in reality, the community’s origins are more diverse. Many also came from other regions, including Uttar Pradesh, Kolkata, Murshidabad, and the Central Provinces of India. Facing threats to their safety and livelihoods, around one million Indian Muslims ultimately sought refuge in what was then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).

After gaining independence from British colonial rule, the people of East Pakistan aspired to democracy, rule of law, equality, freedom, and representative governance. Unfortunately, Pakistan’s subsequent history was marked by military dictatorship, beginning with the abrogation of the Constitution in 1956. As a result, East Pakistan developed a long tradition of democratic movements reflecting these aspirations.

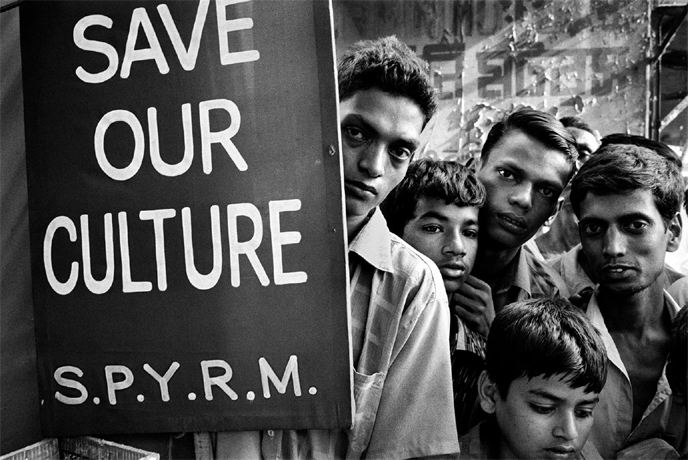

During these struggles, many progressive members of the Urdu-speaking community supported and actively participated in the fight for political and democratic rights. However, a regrettable aspect of history is that their contributions have largely been omitted from the historical narratives written in Bangladesh.

A divided community in 1971

During the War of Independence in 1971, the Urdu-speaking community was internally divided. A significant portion of the community remained neutral and uninvolved, many of them unaware of the rapidly changing political situation.

While one section supported the Pakistan Army, another segment supported the just demands of the Bengali people, believing that political power should have been transferred to them. Over time, a common perception emerged that the majority of the community sided with Pakistan and were involved in atrocities against Bengalis during the conflict in 1971.

Yet the reality was far more complex. As the political situation deteriorated, members of this community – who had migrated from India – found themselves caught in a conflict they did not fully understand and undergone immense suffering. Many faced violence and massacres; their properties and homes were seized or occupied, and they lost businesses and jobs in the aftermath of the war.

Those who survived were often forced to migrate once again – some to Pakistan, while others spread to different parts of the world. Among those who remained in Bangladesh, the community split into two groups: one part chose to integrate into mainstream society in the newly independent country, while the other sought refuge in makeshift camps.

Despite their struggles, both Pakistani and Bangladeshi authorities largely ignored or suppressed these events, each driven by their own political interests.

Camps meant to be temporary became permanent

In 1972, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), a Geneva-based humanitarian organization, stepped in to help protect the community from further loss of life. To support the smooth delivery of humanitarian aid, they first arranged accommodations for the community.

In this effort, they established 116 settlements across thirteen districts, which came to be known as camps. In 1973, the ICRC and the Ministry of Public Works & Urban Development (Public Works Division) of the Government of Bangladesh reached an agreement regarding the accommodation of the community in these camps.

This agreement is documented in a letter, memo No. 31-7/73/167h dated 30 August 1973, which states: “the rehabilitation of non-locals is under active consideration of the Government. It is, therefore advisable to maintain status quo regard now under control of International Red Cross”. The letter further read, “It is requested that, pending final decision, ICRC may be use the houses presently under their control”.

Following this and similar subsequent letters, successive governments of Bangladesh have continued to recognize and respect the community’s right to remain in these camps and to access essential services such as electricity and water provided by the government.

In 1974, a Tripartite Agreement was signed between India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. This agreement acknowledged that the promise of “repatriation to Pakistan” was unlikely to ever fully materialize.

Following this, there was an urgent need for a comprehensive plan to integrate and mainstream the community into Bangladeshi society. In response, progressive members of the community took the initiative to advocate for inclusion. Unfortunately, in 1978, a Mafioso-style leadership emerged within the community.

This leadership misled camp-based residents, ultimately trapping many in makeshift camps where they continued to live in inhumane conditions-disenfranchised and deprived of fundamental rights. Over time, these camps became long-term settlements, with many families enduring extremely poor living conditions for decades. However, the suffering of the community has remained largely unrecognized in official historical accounts.

Legal recognition won – but rights deferred

The community has often been categorized in international legal frameworks as refuges, internally displaced, forcibly displaced, or stateless. However, in the early years of the 21st century – around 2000 – a group of young people from within the community began to challenge the corrupt leadership that had long dominated life in the camps.

Their goal was to secure formal recognition of the community as Bangladeshi citizens and to achieve sustainable, meaningful change, ensuring that future generations could enjoy greater inclusion and fully exercise their fundamental human rights.

In 2001, this group filed a writ petition with the High Court Division of the Bangladesh Supreme Court, arguing that members of the community were Bangladeshi by law but had been discriminatorily excluded from the voter list.

After extensive arguments and hearings, the court ruled in their favor, declaring that the community is indeed Bangladeshi citizens and directing the Election Commission to include their names in the voter list.

After this landmark judgment, elements within the bureaucracy, a section of professionals who strongly promoted Bengali nationalism, and the entrenched Mafioso-style leadership within the community sought to undermine the ruling. They spread the narrative that the judgment applied only to the ten petitioners, creating confusion and doubt.

This uncertainty deepened when, during the “one-eleven” caretaker government period, the authorities decided to introduce National Identity Cards and prepare a new voter list across the country. As a result, the Urdu-speaking community was left uncertain about whether they would be included in this process.

To protect their fundamental rights, a group of eleven community members filed a fresh writ petition in 2007, which resulted in another favorable judgment in 2008 affirming their citizenship and right to franchise. However, despite these clear court rulings, the bureaucracy and the Election Commission remained reluctant to fully include the community in the voter list and national ID card registration process.

In response, organizations such as RMMRU, Al-Falah Bangladesh, and several active community-based groups launched sustained advocacy efforts. A few international organizations including UNHCR and the EU Delegation to Bangladesh, also lent their support, pressing the Election Commission to meet its legal and moral obligations.

A significant breakthrough came in 2008, when the Election Commission made special arrangements to facilitate the inclusion of the community in this process. Collectively, these efforts were driven by the hope of ending decades of marginalization and inhumane conditions lasted in the camps.

In 2008, for the first time, the community exercised their right to vote in the general election while simultaneously urging the government to ensure their “permanent rehabilitation with dignity” within Bangladeshi society.

However, over sixteen years of the Awami League’s rule, the community has largely been mobilized by the ruling party – and by opportunistic leadership within the community itself – solely to vote in favor of the Awami League. No concrete development plans were formulated, and not a single meaningful program was implemented to address their longstanding needs.

There was hope that, once the issue of citizenship was resolved, international development partners would intervene with a comprehensive development action plan. Sadly, in the end, all those hopes proved to be in vain.

A glimpse of hope in the “New Bangladesh”

In July-August 2024, Bangladesh witnessed a monsoon revolution, also known as the mass uprising. Through this movement, the people of Bangladesh expressed their aspiration for a “New Bangladesh” – one where democracy, the rule of law, equality, human rights (including minority rights), and accountability are truly upheld.

In this “New Bangladesh” era, the stories, trauma, and resilience of the Urdu-speaking community deserve to be acknowledged and documented. The dominant narrative has long reinforced negative stereotypes, deepened the community’s political and social marginalization, and overshadowed the diversity of perspectives and lived experiences within the community itself.

As a result, generations of the community in Bangladesh have struggled for recognition – not only as citizens, but also as a people whose history and sacrifices form an integral part of the nation’s broader historical narrative. Despite these challenges, the Urdu-speaking community has continued to preserve a distinct cultural identity, rooted in its language, traditions, and shared social practices.

A call for an inclusive Bangladesh

As Bangladesh enters what many call a “New Bangladesh,” the real test is whether inclusion extends beyond slogans. Will the Urdu-speaking community – and other minorities – be treated as equal citizens?

Perhaps these aspirations may seem overly ambitious for now, but I believe that the coming generations of Bangladesh – with the courage to build a truly inclusive and equitable society – can turn this hope into reality.

(The writer is a NGO practitioner).