Special Report :

A story on the Wall Street Journal published on August 6, 2023 titled: “Rising Money Flows, Fueled by Record Migration, Prop Up Autocrats,” claimed remittance flows fueled by increased migration are creating and perpetuating autocracies around the globe.

The article claimed thatfrom bustling streets of Uganda to the serene landscapes of Nepal, remittances are changing lives.

LIMA, Peru, was abuzz with stories of people from every corner of the world, migrating in unprecedented numbers sending in dollars that were collected by the government which in turn distributed equivalent sums in local currency to their families.

These funds were not just feeding families and supporting small businesses; they were the backbone of many economies.

However, this influx of money was a double-edged sword. While it provided sustenance to the needy, it also propped up autocratic regimes, especially in fragile states.

Venezuela, a nation grappling with economic collapse, saw a third of its households relying on remittances.

Central Asia, with its history intertwined with the Soviet era, depended on these funds to balance their trade deficits. Nicaragua, under the rule of President Daniel Ortega, viewed remittances as a crucial component of its tax revenue.

Enrique Sáenz, an exiled Nicaraguan economist, remarked, “Without remittances, our national economy would crumble, and Ortega would face insurmountable challenges.”

Many remittance-addicted economies as such have lost government incentives to develop competitive domestic industries, create jobs for the youth in the local market, and develop basic services such as healthcare and education.

The dilemma was evident. International reformers aiming to pressure autocratic leaders found themselves in a quandary.

Limiting remittances would inadvertently harm the very families that depended on them. Ryan Berg from the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington voiced this concern, highlighting the complexity of the issue.

Autocratic regimes are being backed by the major autocratic superpowers even though they earn forex from developed nations with affluent populations either through exports or via remittance earnings.

The World Bank reported a staggering increase in remittances to the developing world since 2010, reaching a record $647 billion last year. To put this into perspective, in 2021 Crude Petroleum were the world’s most traded product, with a total trade of $951B according to OEC.

Countries like Nepal, where remittances constituted a significant portion of the GDP, found stability amidst political and social unrest.

Jeevan Baniya, an expert on migration, noted, “Remittances reinforce the existing power structures.”

It is just a matter of time global remittance flows will surpass revenue generated from oil trade. The “black gold” is being overshadowed by the funds being sent by unskilled labor (the “brown gold”) to their families at home.

Growing remittance income by otherwise impoverished economies are also resulting in high-and more relevant-foreign debt to foreign currency income ratios in many parts of the world.

Remittance income is seen as a country’s ability to pay foreign debt obligation by many sovereign funds and global development banks.

Occasionally, borrowing in the name of inflated infrastructure projects have resulted in near bankruptcies of countries such as Sri Lanka.

To make things worse, forex derived from remittance income and foreign debt are fueling money laundering and creating oligarchs in these developing nations.

A research paper titled: “Effect of Remittance Inflows on External Debt in Developing Countries,” by Abdoul’ GaniouMijiyawa&Djoulassi K. Oloufade published on Open Economies Reviews on July of 2022 has shown there is direct correlation between remittance income as a percentage of GDP, and foreign debt.

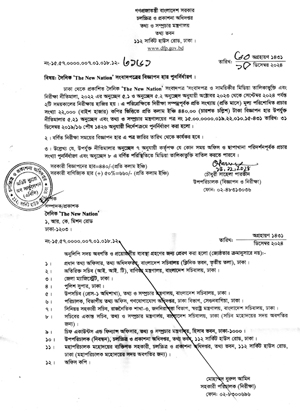

Meanwhile, in Bangladesh, the geographically tiny nation that ranks No.7 in terms of global remittance receipts, a significant player in the remittance landscape, there was a notable inflow of nearly 2 billion U.S. dollars in July 2023.

Despite a year-on-year decline of 5.86%, the Bangladesh Bank expressed satisfaction, attributing the usual surge in remittances to major Muslim occasions like Eid-al-Fitr and Eid-al-Azha.

In June, buoyed by the relaxation of various rules and the celebration of Eid-al-Adha, the country saw an inflow of 2.2 billion dollars, the highest in nearly three years.

The annual remittance for the fiscal year 2022-2023 through formal channels alone stood at a commendable 21.61 billion dollars, primarily from Middle Eastern countries.

By far, on a net basis, Bangladesh’s main source of forex has become its migrant workers around the globe.

In a broader context, an empirical study delved into the long-term impact of various factors, including remittance outflows and oil prices, on the real GDP of GCC countries from 2000 to 2019.

The study utilized the augmented mean group (AMG) method, an advanced econometrics technique.

The findings revealed a significant long-run relationship between the selected variables, especially with non-oil real GDP.

The results emphasized the influence of sudden falls in oil prices, such as the 2015 drop, on the economies of GCC countries.

The study also highlighted the negative impact of increased remittance outflows on non-oil real GDP.

Given the unique characteristics of GCC countries, with their oil-dependent economies and pegged exchange rate regimes, the study proposed that non-hydrocarbon sectors might respond differently to changes in oil prices and remittance outflows.

The research underscored the need for policymakers in GCC countries to consider the structure of their foreign labor force and its impact on remittance outflows.

The study recommended implementing a more effective nationalization process, promoting economic diversification, and leveraging the region’s financial resources to achieve sustained economic growth.

But beyond the economic implications, remittances are also emerging as a powerful weapon against dictatorships.

A recent book titled “Migration and Democracy: How Remittances Undermine Dictatorships” by Abel Escribà-Folch, Covadonga Meseguer, and Joseph Wright argues that global migration may be one of the most potent drivers of democracy.

By allowing people to move, work, and share what they earn, remittances facilitate protest, undermine authoritarian electoral strategies, and tip the balance of power towards citizens mobilizing for democratic change.

The migrant workers can easily force governments to change its policies and practices by choking the economy through forex starvation.

In Sri Lanka for example, one the main reasons for the collapse of Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s government was seen as drying up of remittance flows through formal channels.

The decentralized nature of remittances, controlled by the people who send and receive them, increases the likelihood of protests and reduces support for dictatorial regimes.

The authors combine global macro-analysis with individual-level microdata and case studies, such as Senegal and Cambodia, to demonstrate that remittances favor democratization processes in receiving countries.

The authors stress the exchange of ideas that occurs when immigrants settle in advanced democracies, leading to democratizing effects in their home countries.

They explain how remittances empower citizens demanding democracy, serving as resources to mobilize political opposition.

The analysis of data from 17 African countries ruled by autocratic governments in the past two decades shows a positive relationship between remittances and anti-government protests.

The authors conclude, “Global migration funded the kind of political action that has most helped lead to peaceful democratization over the last quarter of a century.”

As the world grapples with the intertwined destinies of migrants, remittances, and regimes, the stories from LIMA to Nicaragua underscore the complexities of global migration and its far-reaching impacts.

The emerging narrative of remittances as a force for democracy adds a new dimension to the conversation, highlighting the potential for positive change in the global political landscape.