‘Case Jam: The Silent Crisis of the Judiciary’

Rokon Bappy :

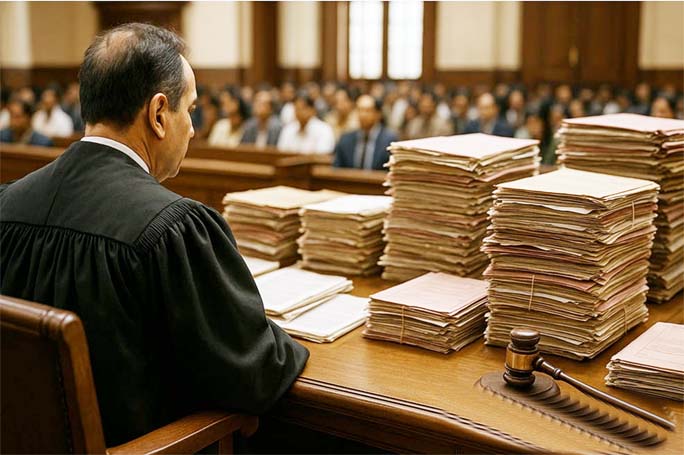

Case Backlog in all courts of Bangladesh is a kind of crisis which highlights a deep and long-standing problem in the Bangladesh Judicial System. The judiciary of Bangladesh is today immersed in a silent but deep crisis.

Thousands of people wait in the courtroom every day in the hope of justice, but even after years, their cases are not resolved. Delay in getting justice means not only administrative failure, but it is a subtle form of depriving citizens of the fundamental right to justice. The number of pending cases in the lower courts alone is in the millions. On average, it takes about five to ten years, sometimes more, to resolve a civil case. The same is true in criminal cases—witnesses not appearing, police reports being delayed, or lawyers asking for time, all of which almost bring the progress of the case to a standstill.

There are multi-layered reasons behind the backlog of cases. The judge crisis is one of them. Currently, the number of judges and magistrates is less than half of the required number, which is largely responsible for the delay in trial. Inadequate infrastructure and technology are also contributing to the backlog of cases in various ways. Many courts still do not have electronic document management; as a result, problems such as losing or not finding case files frequently arise. Due to the time-wasting culture of lawyers and police, the practice of filing cases after dates slows down the pace of the case. Sometimes, parties deliberately prolong the case for their own benefit.

In addition, due to procedural complexities, a case has to go through numerous steps from the initial investigation to the appeal, which is also very time-consuming and expensive. The greatest loss due to all these delays in trials is caused to the common man. People are mentally, financially and socially devastated due to cases being pending for years. In some cases, people are forced to take the law into their own hands, which creates distrust in the rule of law in society. It also has a devastating impact on the economy.

Besides, delays in resolving business disputes create a reluctance to foreign investment, and private property litigation makes the use of land or resources uncertain. As a result, this stagnation in the judicial system also hinders the overall development of the country.

Possible solutions, relevance of reforms and practical paths

The backlog of cases is not just an administrative problem; it is also a manifestation of the structural limitations of the judicial system in Bangladesh. Therefore, its solution requires not only technology, but also institutional reform of the judicial system. Since independence, the judicial system has largely survived on a colonial structure where the process is complex, documents are paper-based, and the pressure on the judge is disproportionate. No matter how much society and technology change, the judicial process continues at its old pace. As a result, delayed justice has now become a tradition.

In this context, modernization of the judiciary is not only necessary—it is a structural reform that demands time, which will bring justice to a dynamic, affordable, and accessible to the people. First, it is necessary to introduce a technology-based court system (e-judiciary). It is possible to speed up the case process through e-filing, online case tracking, and video testimony. The experience of launching virtual courts during the Corona pandemic has shown that if technology is used properly, the trial process does not stop, but rather becomes more effective.

Second, increasing the number and capacity of judges is essential. Currently, one judge has to handle the cases and disputes of about 90,000 citizens—which is practically impossible. Regular recruitment, training, and efficiency in case management must be increased.

Third, the Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) system must be further expanded. If family, civil, and small commercial disputes can be resolved through out-of-court settlements, the pressure on court cases will be significantly reduced.

Fourth, the accountability of lawyers and the judiciary must be ensured. Many times, lawyers’ repeated requests for time or the absence of witnesses hinder the progress of cases. Fixed deadlines and digital monitoring systems can be introduced in court proceedings, so that the progress of each case can be seen transparently.

Finally, the institutional independence and policy-making autonomy of the judiciary must be increased. Effective reforms are not possible without an administrative structure free from executive influence.

The Judiciary Reform Commission formed by the government has made some basic proposals in its recent report. These include establishing permanent High Court benches in each division, expanding the lower courts, professionalizing the government lawyer service, introducing a case-management system for initial review and prioritization of cases, and increasing autonomy in judicial administration. On the other hand, the Judiciary Roadmap (2024–2025) published by the Chief Justice has given directions for digital transformation of the court system, setting a time limit for speedy disposal of cases, expanding video testimony, and increasing the use of information technology in court administration.

These initiatives have been taken with the aim of modernizing the judicial process as a whole. However, the success of these reforms depends on a deep policy change where the courts become not just courts, but also a symbol of citizen trust. There are some international standards for measuring judicial efficiency and access to justice worldwide.

The Council of Europe’s CEPEJ (European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice) guidelines state that the time to access justice should be within reasonable limits, that the proceedings of the courts should be transparent and open to the public, and that information should be easily accessible to citizens. The World Bank has also identified four key pillars of judicial reform—autonomy, transparency, accessibility, and technology.

In addition, to ensure the right to information, it is important to make court statistics, case disposal information, judges’ activities, and the progress of the roadmap open to the public. If data is published regularly on the court website and e-judiciary portal, not only will the public gain confidence, but public support for reforms will also increase. In addition, judicial awareness programs can be launched with the media, educational institutions, and civil society, so that the common people understand in simple terms that judicial reform does not only mean increasing the speed of cases—but also improving the quality of justice.

After all, it can be said that the judiciary is the backbone of a state. If there is stagnation in that backbone, the foundation of justice, order, and trust in the state also becomes shaky. The backlog of cases is not only a problem of the court, but it is a reflection of the moral and administrative crisis of the nation.

The time has come to make the judicial process timely, dynamic, and humane. Without ensuring speedy, affordable, and accessible justice, the word “justice” will remain confined to the pages of law books, not in the lives of citizens.

(The writer: Apprentice Lawyer, District & Session Judge Court, Dhaka (LL.B JKKNIU), Researcher, Institute of Nazrul Studies, Old Town, Dhaka)