Electioneering starts for 13th JS polls sans posters

Abu Jakir :

Campaigning for the much-anticipated 13th parliamentary election formally began on Thursday, ushering in a season unlike any the country has seen in decades.

With the Election Commission completing the allocation of electoral symbols to political parties and independent candidates, the long road to the February 12 polls opened not with walls layered in posters, but with prayers, walking processions and appeals for direct connection with voters.

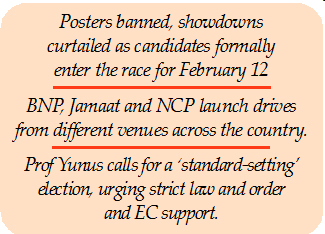

The three major political forces—BNP, Jamaat-e-Islami and the National Citizens’ Party (NCP)—marked the first day of campaigning from different corners of the country, signalling both the diversity of the contest and a shared recognition that this election will be fought less on billboards and more on doorsteps.

BNP Chairman Tarique Rahman launched his party’s campaign in Sylhet by offering prayers at the shrine of Hazrat Shahjalal, a symbolic beginning that party leaders said reflected a desire to seek blessings before taking their message directly to the people.

In Dhaka, Jamaat-e-Islami chief Dr Shafiqur Rahman began his party’s campaign with a rally in Mirpur. The National Citizens’ Party opened its drive with visits to the Mausoleum of Three Leaders and the grave of Osman Hadi, before leading a procession toward the National Press Club.

Across the country, candidates are now preparing to fan out into neighbourhoods and villages—not to paste posters, but to knock on doors.

For generations, the onset of an election in Bangladesh was unmistakable. Markets, roadside trees, alleyways and walls would disappear beneath layers of paper bearing faces, symbols and promises. Posters were once the most visible declaration that the race had begun, transforming public space into a sprawling political gallery.

That landscape will be missing this time.

Ahead of the February 12 vote, the Election Commission overhauled the electoral code of conduct, banning posters outright and sharply limiting the use of vehicles, convoys and mass showdowns.

The changes are pushing candidates toward a quieter but potentially more intimate style of campaigning—one centred on walking tours, small courtyard meetings and direct conversations with voters.

Under the revised rules, posters are prohibited in all forms. While leaflets, handbills and banners remain permissible, they may not be affixed to buildings, walls, trees, fences, utility poles, government installations or vehicles. Each candidate is allowed a maximum of 20 billboards within their constituency, a ceiling that drastically reduces the dominance of large-scale visual advertising.

Mechanised campaign convoys—buses, trucks, boats, motorcycles and torch processions—are banned. Helicopters and other aircraft may only be used by a party’s president and general secretary, while drones are completely prohibited. Even during nomination submission, processions and showdowns are not allowed.

Election officials say the intent is to curb environmental damage, reduce campaign-related conflict and create a more level playing field. Posters, often laminated, have long been blamed for blocking drainage systems, contributing to waterlogging and damaging farmland through ink runoff, while disputes over campaign materials have frequently sparked clashes.

Election Commission Secretary Akhtar Ahmed has said political parties were consulted before the changes were finalised, noting that, except for one party, none objected to the ban on posters. He added that the Election System Reform Commission had earlier recommended prohibiting posters in elections.

The new rules do not confine campaigning to the physical world alone. For the first time, social media campaigning has been formally incorporated into the code of conduct, bringing online outreach under explicit regulatory oversight. Candidates, their agents and parties must register their social media platforms, account IDs and contact information with returning officers before beginning digital campaigns.

The use of artificial intelligence with dishonest intent is explicitly restricted. The code bans misinformation, hate speech, personal attacks, manipulated images, fabricated election content and material targeting women, minorities or any other group.

Religious or ethnic sentiments may not be exploited, and election-related content must be verified before being shared.

Yet election officials have stressed that digital tools are not meant to replace human contact. With public meetings regulated, microphones limited and mass showdowns curtailed, the Commission expects candidates to prioritise personal outreach—listening to local concerns in living rooms, courtyards and tea stalls rather than projecting slogans from walls and stages.

The scale of the contest is vast. According to draft Election Commission data, 1,967 candidates—from around 50 political parties as well as more than a hundred independents—are set to contest the election across 298 constituencies.

The figure was finalised after the withdrawal deadline on Tuesday, when 305 candidates pulled out, said Md Ruhul Amin Mallik, director of the EC Secretariat’s public relations wing. Nomination submission closed on December 29, with 2,585 papers filed across 300 seats.

Voting is scheduled for February 12, from 7:30am to 4:30pm.

Candidates wishing to hold public meetings must notify authorities at least 24 hours in advance, specifying the time and venue.

No more than three microphones or loudspeakers may be used at a single gathering. Violations can result in fines, imprisonment of up to six months, or even the cancellation of candidacy under the Representation of the People Order.

As the campaign season opens, the absence of posters is already reshaping the political atmosphere. The familiar riot of colour and paper has given way to something quieter—and potentially more consequential. With visibility no longer guaranteed by glue and ink, success may depend on patience, presence and persuasion.

From Sylhet’s shrines to Dhaka’s neighbourhood lanes, candidates are beginning the slow work of meeting voters where they live. In an election stripped of much of its spectacle, Bangladesh’s political contest is moving closer to its people—one doorstep at a time.

As campaigning gets underway, the interim government has sought to frame the February 12 vote as a defining test for the nation.

Chief Adviser Professor Muhammad Yunus on Thursday stressed that the forthcoming general election must be held in a way that sets a new benchmark for Bangladesh.

“The 2026 polls should be such an election that will set a standard for future elections,” he said.

Prof Yunus made the remarks while chairing a high-level meeting on the overall law and order situation at his office in the capital’s Tejgaon area, ahead of the 13th Jatiya Sangsad election and the referendum on the implementation of the July National Charter.

His Press Secretary, Shafiqul Alam, later briefed reporters on the discussions at the Foreign Service Academy.

“Our task is actually to assist the Election Commission,” Prof Yunus said at the meeting. “This is a major challenge for the nation, which we must take on, and we must complete this huge task and establish it as a historic achievement.”

Emphasising operational readiness, he said utmost attention must be paid to ensure there is no shortfall on polling day. “There must be no lapses anywhere on February 12,” he said.

“Our step-by-step tests have started ahead of the elections. Starting from today, the final test will be held on February 12,” the Chief Adviser added.