Celebrating Victory in a New Reality

Syed Tosharaf Ali :

The passage of time is truly strange. Human beings create history, and then again alter the course of living history.

Much like a river changes its bends, history too changes direction. People try to shape history with hope and belief, but sometimes—like sculptors trying to create Shiva and ending up with a monkey—things go terribly wrong.

In truth, when human beings attempt to turn their abstract thoughts and perceptions into reality and discover that reality does not match what they had imagined, their dreams shatter. And then—what is left to do?

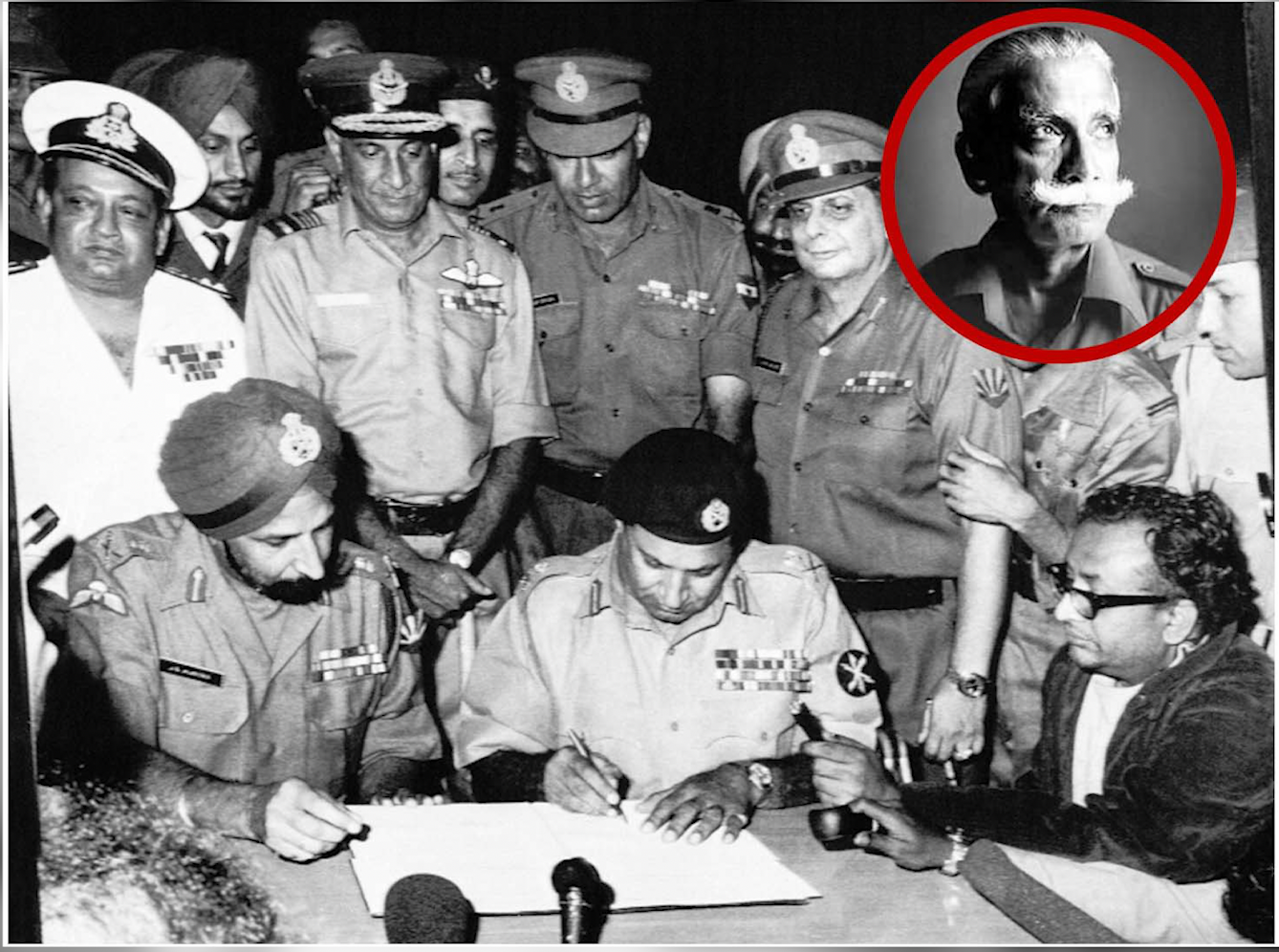

After a long struggle, in 1947 we obtained a moth-eaten Pakistan. And in 1971, after crossing a river of blood, when we reached the shores of liberation and the Pakistani army surrendered to the Allied Forces, General A.K. Niazi stood beside General Jagjit Singh Aurora—but the Commander-in-Chief of the Liberation War, General M.A.G. Osmani, was nowhere to be seen. So many hopes, so many dreams, so much struggle, so many tears and so much blood went into writing that history, yet General M.A.G. Osmani remained absent from it. India honored Manekshaw with the title of Field Marshal as the victorious general, but regrettably Bangladesh did not honor General Osmani with the rank of Field Marshal.

In 1971, forced to fight the modern, well-armed and trained Pakistani army, we had no option but to seek India’s help. Whether we understood it then or not, we entered India’s sphere of influence. As a result, we first had to accept the ideology of democracy, socialism, and secularism of the then government and the Indira Congress. Nationalism—the very foundation on which the struggle for the establishment of Bangladesh had begun—had to be abandoned. How influence arrives disguised as assistance is something we learned through experience.

Recall those days of 1971, when on November 23 General Yahya Khan declared that if India did not stop helping the Bangladesh Liberation War, Pakistan would attack India within ten days. Faced with this threat, Tajuddin Ahmad’s government-in-exile discussed the matter internally.

Since the government-in-exile was sheltered and supported by India, it was naturally dependent on India. Therefore, to determine the course of action, “one night, unnoticed by everyone, Syed Nazrul Islam Sahib and I disappeared from Mujibnagar (Calcutta). After a long night of discussion with Mrs. Gandhi, we jointly informed India of our intention to fight together.”

(Tajuddin Ahmad’s lecture at Bangla Academy, December 16, 1973)

However, problems arose later when the question of forming a joint command emerged. Why Tajuddin Ahmad did not mention this issue in his speech is beyond our understanding. One day, when Tajul Islam and I raised this issue in a discussion at General Osmani’s Old DOHS residence, he narrated many stories. During his stay in Calcutta, some people tried in various ways to humiliate him. He said he was most astonished when the matter of fighting jointly was placed before the cabinet for approval, and as Commander-in-Chief of the Mukti Bahini his opinion was sought. He demanded the formation of a joint command. Sadly, only one cabinet member supported him; the others remained silent. Since the matter was directly related to sovereignty, he said, there was no room for flexibility on his part.

Indian Army Chief General Manekshaw and Eastern Command Chief General Jagjit Singh Aurora were not in favor of forming a joint command. He was belittled, yet he responded to their sarcasm with due dignity and remained firm in his position. Eventually, the deadlock was resolved through the positive roles played by Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s Principal Secretary P.N. Haksar and Political Secretary D.P. Dhar.

The distance created by that controversy over the joint command was reflected later in the absence of Mukti Bahini Commander M.A.G. Osmani at the Pakistani General Niazi’s surrender ceremony at Suhrawardy Udyan in Dhaka—despite his presence being essential. Yet the matter did not receive due importance. The explanations offered were essentially attempts to cover fish with conch shells. Indian diplomat J.N. Dixit, however, admitted in his book Beyond Liberation that this was a mistake on India’s part.

In recent times, when some Indian leaders in responsible positions portray the emergence of Bangladesh as merely a product of the Indo-Pak war and try to downplay the role of the Liberation War, freedom fighters feel deeply uncomfortable and angered. Claims of Indian assistance in the name of independence, democracy, and humanitarian values also come under question.

In 1974, political instability intensified, social peace vanished, and theft, robbery, and terror politics robbed villagers of sleep. Instead of forming an all-party government, the Second Revolution was declared, and solutions were sought through establishing an extreme authoritarian one-party BAKSAL system. The democratic character of the constitution was altered without debate.

Press freedom was curtailed, most newspapers were shut down, and the judiciary was placed under executive control. People watched these unprecedented changes with silent anguish. With all constitutional paths for changing government blocked, the military intervened, leading to bloodshed and prolonged military rule. Democratic norms and institutions never got the time to take root.

Even today, we await an independent judiciary, free media, independent elections, an autonomous Anti-Corruption Commission, and Public Service Commission. Transparency and accountability in public procurement are absent. Despite some power transitions under caretaker governments, democratic rhythm eventually broke down. Despite being neighbors to the world’s largest democracy, we never received support from it in establishing democracy.

Influence and interference repeatedly hindered our development. Projects prioritizing neighboring interests were undertaken, offering transit facilities and access to Chittagong and Mongla ports without significant financial returns—what a former foreign minister once described as a “husband-wife relationship.”

How, in the name of Liberation War ideals, the hopes of the people of this country—won through tears and blood—were sacrificed is a long story, impossible to fully recount here. Much of it you already know: banks looted, reserves plundered, stock markets ruined—all by those close to power. Reports of their amassed wealth now astonish even the super-rich and enrage educated youth. It is now clear why protesters were jailed, disappeared, or killed; why fear and incentives were used to subdue judges, intellectuals, journalists, professionals, and bureaucrats; why voting rights were denied; why elections were rigged; and why opposition movements were brutally crushed.

After the farcical election of 2024, when despair over confronting fascism prevailed, Dhaka University students revived an old suspended movement—the anti-quota movement in government jobs. No one initially imagined the wildfire it would spark. The brilliance of today’s generation became evident as they systematically transformed it into a movement to topple the government. Streets turned into battlefields.

Orders were given to suppress protests with lethal weapons. Roads were soaked in blood; hundreds were killed and injured—UN reports estimate 1,400 deaths. Further bloodshed was intended, but when soldiers turned, the situation dramatically changed. Sheikh Hasina left Bangladesh and an interim government took oath under the leadership of Prof. Dr. Muhammad Yunus and he is running the government with confidence. National election is going to be held on the 12th February 2026.

We hope this noble initiative succeeds—leading Bangladesh back onto the democratic path through promised elections, ending politics of hatred, and revitalizing trade, agriculture, industry, and the economy.

The youth who made this struggle victorious have restored national confidence. The learned and wise now have the opportunity to govern—and no room to fail. Youth power is the future of this country, and it must be protected. At this critical moment, the people desire unity like a mountain—not division. Hope and struggle are our provisions for the journey. In this new reality, we shall celebrate victory.

(The author: Bir Muktijodddha and Advisory Editor, The New Nation.)